About Atlanta

Local Attractions

Atlanta History

|

Atlanta is a young city, even by American standards. New Orleans, Charleston, Cincinnati and Chattanooga were all thriving cities before Atlanta was even a settlement. Atlanta is a bright, brash, aggressive town; tempered by fire, its rough edges smoothed by time and dashing with southern charm. Despite its relative youth, Atlanta has a proud and unique heritage and a past well worth preserving.

Atlanta is a young city, even by American standards. New Orleans, Charleston, Cincinnati and Chattanooga were all thriving cities before Atlanta was even a settlement. Atlanta is a bright, brash, aggressive town; tempered by fire, its rough edges smoothed by time and dashing with southern charm. Despite its relative youth, Atlanta has a proud and unique heritage and a past well worth preserving.

From the beginning, Atlanta was in the South but not of the South. Founded as a rail terminus, ante-bellum Atlanta was a small, rough-and-ready railroad crossing. Its manners and mores were more like the frontier towns of the Old West than the mint julep and magnolia cities of the Old South. Transportation was, and still is, the catalyst for Atlanta's growth and economic vitality. From the beginning, Atlanta attracted men and women of vision---opportunists who had the foresight to provide the facilities that would make Atlanta the most important city in the Southeast.

Over 150 years ago, the land that is now Atlanta belonged to the Creek and Cherokee Indians. The United States was well into the War of 1812 when the first white settlement, Fort Peachtree, was established on the banks of the Chattahoochee River near the Cherokee village of Standing Peachtree. The Creek Nation ceded their lands to the State of Georgia in 1825. The Cherokees lived with their white neighbors until 1835 when the leaders of the Cherokee nation agreed to leave their lands and move west under the Treaty of New Echota. At that time, Georgia officially took possession of Cherokee lands, an act that led to the infamous Trail of Tears.

Early settlers in the Atlanta area were farmers and craftsmen from Virginia, the Carolinas and the mountains of North Georgia. They obtained their land by lottery disbursement and were, for the most part, deeply religious, hard-working, small landholders. They owned few slaves and lived in harmony with their Indian neighbors. They established churches and schools, traveled to Decatur for "store-bought" goods and marketed their cotton in Macon, 100 miles south.

They were as close to a yeoman (small farmers/craftsmen) society as possible in the ante-bellum South. A few of their pre-Civil War homes, churches, cemeteries and mills still exist in the Metropolitan Atlanta area. Atlanta's inception was a combination of geography and necessity, spawned by the steam engine. In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly voted to build a state railroad to provide a trade route from the Georgia coast to the Midwest. The sparsely settled Georgia Piedmont was chosen as the terminal for a railroad that was to run "from some point on the Tennessee line near the Tennessee River, commencing... near Rossville... to a point on the southeastern bank of the Chattahoochee River" accessible to branch railroads. The new railroad was to be called the Western and Atlantic Railroad of the State of Georgia.

An experienced army engineer, Colonel Stephen Harriman Long, was selected to choose the most practical route for the new rail line. After thoroughly surveying half-a-dozen routes, Long found it necessary to choose a site eight miles south of the river where connecting ridges and Indian trails converged. He drove a stake into the red clay near what is now Five Points in Downtown Atlanta. The "zero milepost" today is marked by a plaque not far from that very spot in Underground Atlanta. The site staked out by Colonel Long proved to be perfect, the climate ideal. Atlanta is situated on the Piedmont Plateau at an elevation of 1,050 feet, yet there are no natural barriers such as mountains or large bodies of water to impede the city's growth.

In the fourteen short years between the time Colonel Long drove his marker into the ground and the start of the Civil War, Atlanta grew like the boom towns of the West. Instead of mining, Atlanta struck gold in the rail lines.

The little settlement of railroad workers, aptly named Terminus, soon attracted merchants and craftsmen, salesmen, land speculators and opportunists. Banks, warehouses, sawmills, a fledgling textile industry and ironworks soon followed. The city was re-named Marthasville in honor of Governor Lumpkin's daughter. A few years later, prominent citizens decided that Marthasville was too long and too bucolic a name for such a progressive city and the name was changed to Atlanta.

Residential patterns were forming. Mechanicsville grew up around the railyards; a substantial merchant-residential community. West End was established near White Hall Tavern. Residential avenues of affluent citizens began to form as luxurious homes were built on lower Peachtree, Whitehall, Marietta, Broad and Washington Streets.

But pre-war Atlanta was far from a quiet business community. To quote Atlanta historian Franklin Garrett: "while the number of good, moral citizens was increasing... the town was characterized as tough. It grew distinctively a railroad center with the vices common to rough frontier settlements. Drinking, resorts, gambling dives and brothels were run wide open... and the sporting element were insolent in their defiance of public order." There were more saloons than churches; more bawdy houses than banks.

The War Years

Atlanta had already attained a position of regional importance when the Civil War erupted. The city had four rail lines, a population of some 10,000 persons, 3,800 homes, iron foundries, mills, warehouses, carriage and wheelwright shops, tanneries, banks and various small manufacturing and retail shops. It became the supply and shipping center of the Confederacy. Atlanta had all the facilities that made it necessary for Sherman to take the city and destroy it.

General William Tecumseh Sherman began his drive to Atlanta from Chattanooga in July, 1864. After a series of bloody battles and a month long siege of the city, Atlanta surrendered on September 2. The city was in flames, but not entirely due to Union shells. Retreating Confederate troops blew up 81 boxcars of explosives, creating the blaze made famous in the spectacular fire scene in the film "Gone With The Wind." Sherman ordered the city evacuated and all buildings of possible use to the confederacy destroyed. When Sherman began his march to the sea, only 400 structures were left standing. Atlanta was a ghost town of rubble and ashes.

The city was still smoldering when Atlantans returned and started rebuilding. The spirit that made Atlanta the hub of Southeastern commerce- the confidence in Atlanta's future- was stronger than ever. Five years after the holocaust, Atlanta was rebuilt and had more than doubled its pre-war population.

Post-War Growth

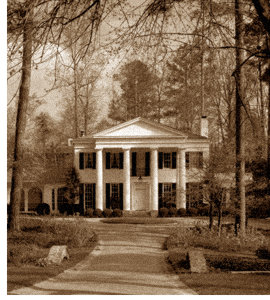

Since the Battle of Atlanta had effectively wiped out most of the city's ante-bellum architecture, Atlanta was rebuilt in the various Victorian styles popular in that era. Ironically, of the few fine white-columned mansions in downtown Atlanta left intact by the war, two were demolished shortly thereafter to be replaced by city and state buildings. The city limits were initially circular, extending one mile from the zero milepost. Initial expansions of the city limits were circular, too. Early demographic patterns were re-established along much the same lines as before the war. West End continued to grow as an upper-class residential-business community. Wealthy white citizens built their Victorian mansions along Washington and Peachtree Streets.

In spite of the system of segregation, prosperous black enclaves emerged, concentrated after 1906 along Auburn Avenue-the "Sweet Auburn" district. Other black neighborhoods developed in Summerhill, Vine City and many more residential pockets surrounding the central city.

From the end of the Civil War through the 1890's, Atlanta experienced rapid growth. By the end of the 1870's, the central business district spread from Union Depot toward the city limits. The city developed along the rail lines and around the depot. A wide path of railroad tracks cut right through the center of town, converging in the lower downtown gulch. A network of viaducts, planned in the early 1900's and completed a quarter-of-a-century later, was built to facilitate the flow of traffic over the tracks. The viaducts moved the business district up one level, thereby creating the area now known as Underground Atlanta.

A simple, utilitarian Italianate architecture was favored for Atlanta's railroad depots and influenced the design of the two and three story commercial buildings constructed before the turn-of-the-century. The railroads continued to be the cornerstone of Atlanta's economy through this period and into the automobile age and through World War II, when emphasis shifted to truck and air travel transport. Transportation and private enterprise spurred the city's growth. Several new rail lines were added to Atlanta's network in the 1890's. The consolidation of ten radiating lines in that decade, including five divisions of Southern Railway, definitely established Atlanta's dominance as the railroad center of the southeast.

When the nation's economy stalled in the doldrums of recession and depression starting in the 1880s, an Atlanta promoter staged a series of fairs and expositions to bring business to this area. The International Cotton Exposition of 1881 was staged to promote Atlanta as a textile center and lure mills from New England in an attempt to build a new economic base in the post-war South by diversifying from the region's agrarian base. The Piedmont Exposition of 1881 was a regional show to publicize the Piedmont States' products and establish closer ties between agriculture and industry. The Cotton States and International Exposition of 1895, specifically proposed to counteract depression, advertised Atlanta as a transportation and commercial center. Historians consider the Exposition of 1895 a most important factor in Atlanta's emergence as the major city of the Southeast, based on Henry Grady's "New South" movement to re-enter the economic mainstream of American life. The Exposition gained world-wide publicity and by 1903 Atlanta was the headquarters for many national and regional companies.

The fair and exposition had the desired effect on Atlanta's growing industrial base as contrasted with the rest of the agrarian-oriented South. Textile mills came south, industrial complexes were built along the rail lines and mill villages were built to house the workers. One of the oldest and largest cotton mills is the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills (c. 1881). Its mill housing district, Cabbagetown, is located within two miles of downtown Atlanta. Workers from the mountain counties of North Georgia, attracted by mill wages, left their Appalachian homes to settle here. The mill owners provided housing and health care. Cabbagetown, a six-block-square area in the shadow of the mill buildings, is characterized by narrow streets, large shade trees, simple frame one and two-story shotguns and cottages with Victorian styling in porch, door and window designs.

A forerunner of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills was the Exposition Mill, which is now demolished. The Exposition mill was built on the former site of Oglethorpe Park as the main building for the International Cotton Exposition of 1881, with a view to its ultimate use as a cotton mill. The Exposition building was sold to a group of businessmen a few months after the show closed and soon was put into production. It developed into one of the most important mills in the area. Other historic mills still standing in Atlanta are the VanWinkle Gin and Machine Company (c. 1893) and the Whittier Mill (c. 1900), along with some of its mill houses.

Atlanta's residential perimeters were expanded by the advent of the horse-drawn streetcar in 1871 and suburban patterns developed along the lines of the electric streetcar starting in 1891.

At the same time, several major private developers emerged. Among these early Atlanta builders was Joel Hurt, who built Atlanta's first "skyscraper," as well as the eight-story Equitable Building and Inman park, Atlanta's first planned residential suburb. At the suggestion of architect John Root, who was then designing the Equitable Building, Hurt invited Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture, to Atlanta for consultation. Olmsted had already won national recognition for his natural terrain designs of New York's Central Park and Riverside Park in Chicago and his influence is evident in many of Atlanta's parks and residential areas. Inman Park was actually designed by landscape gardener Joseph Johnson; but the plan strongly reflects the Olmsted influence. The design is faithful to the natural terrain, with curved streets developed around open park areas.

Edgewood Avenue was built in a straight line to connect Inman Park to downtown Atlanta and Hurt installed Atlanta's first electric streetcar on Edgewood to serve his new suburban community. Olmsted's firm also designed the suburb of Druid Hills and influenced the Ansley Park plan.

During this same period, the early 1880's, Confederate Colonel Lemuel P. Grant donated land to the city for Grant Park. Replacing Oglethorpe Park, it is Atlanta's oldest public park extant. Piedmont Park was initially part of the Gentlemen's (Piedmont) Driving Club. Members of the Club were a leading force in Atlanta's progressive development. The land was leased to the Exposition Company for the Cotton States Exposition in 1895 and later became a public park. The Olmsted Brothers re-designed the park in 1910.

Beginning with the Equitable Building, Atlanta quickly followed the Chicago School of architecture in the development of skyscrapers of "elevator buildings." The new high-rise buildings transformed the city's skyline from picturesque High Victorian to a cluster of multi-use skyscraper hotels and office buildings. The new skyscrapers attracted large railroad and insurance interests. Since office workers generally earned higher wages than factory or farm workers, the office buildings generated a demand for large retail stores and hotels to serve an increasing number of travelers to the city. It was not until after the World War I that businessmen began to look at office buildings as an investment. This led to the building boom of the 1920's. A system of viaducts, conceived by architect Haralson Bleckley in 1901 and completed in 1928-1929, bridged the railroad gulch and raised the street level of downtown Atlanta. The original plan, conceived in the City Beautiful Beaux Arts tradition, included boulevards, walkways and parks.

The Great Depression had an architectural style all its own: Art Deco-Modern. Although building starts were sharply curtailed during this period of national economic hardship, a few of the commercial buildings that were constructed from the 1930s to World War II reflected the new Art Deco styling. Most residential buildings of the decade clung to the revival styles of architecture.

The early commercial buildings and the Victorian and post-Victorian homes built in the 1890 to 1930 period give Atlanta its distinctive personality. Many of these structures are potentially viable today and could be preserved, restored and rehabilitated for contemporary uses. The viaducts, which created the area now known as Underground Atlanta, and Plaza Park, completed in 1950, are the only elements of the Bleckley Plaza plan ever completed.

A variety of architectural styles evolved between 1890 and 1930, following national trends reviving elements of Gothic, Classical and Colonial styles. Turn-of-the-century revival architecture includes Beaux Arts Classicism, Neo-Classical, Tudor-Jacobean, Renaissance Revival, Colonial Revival and Commercial styles. In addition, Bungalow-Craftsman and 20th Century Vernacular-Plain styles emerged. There are many fine examples of these varied styles of architecture created by outstanding architects and craftsmen still standing in Atlanta. Excellent examples of homes constructed during this era of suburban growth may be found in the Druid Hills, Buckhead and Ansley Park neighborhoods.

Without these beautifully detailed old structures, Atlanta would be Anywhere, USA- a skyline of high-rises, round and square, pre-stressed concrete and mirrored glass sameness.

Atlanta is the Capitol city of the southeast, a city of the future with strong ties to its past. The old in new Atlanta is the soul of the city, the heritage that enhances the quality of life in a contemporary city. Without these artifacts of our culture, Atlanta would simply not be Atlanta. In the turbulent 60's, Atlanta was "the city too busy to hate." It must never become the city too busy to care.

Courtesy of the Secretary of the State of Georgia

|